CU Boulder Alumna Sristy Agrawal’s Mesa Quantum Navigates to Success with Quantum Technology

Mesa Quantum, a quantum sensing company and CU Boulder spinout, is making waves in the tech world. The company recently secured $3.7 million in seed funding, alongside a $1.9 million grant from SpaceWERX, the U.S. Space Force’s innovation arm. These investments are driving Mesa Quantum towards commercializing its chip-scale quantum sensors. These advanced sensors have the potential to revolutionize several applications, with a specific focus on next-generation positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) solutions.

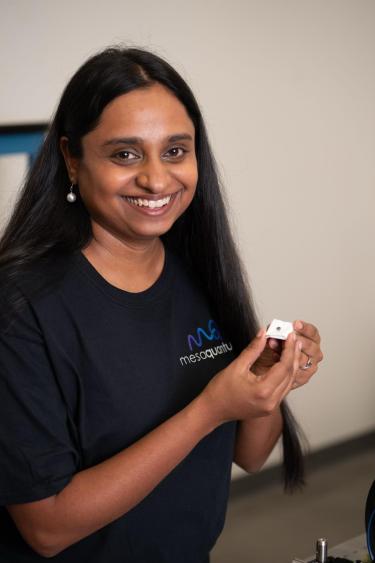

Sristy Agrawal, CEO and Co-founder of Mesa Quantum.

Sristy Agrawal, co-founder and CEO of Mesa Quantum shared her excitement from the company’s new Boulder headquarters. Agrawal, who holds affiliations with NIST, JILA, and CU Boulder Physics, is understandably energized by the progress. She’s been traveling extensively, attending conferences across the U.S., Europe, and Asia to discuss her company’s groundbreaking technology and its potential impact.

“We want to make sure that our roadmap and our product development ensures we’re not just developing a cool technology but also solving a real problem,” Agrawal explained.

One critical problem Mesa Quantum aims to address is the vulnerability of the U.S. Global Positioning System (GPS), which is often the primary source for PNT services. Accurate GPS and PNT systems are fundamental to daily life, from mapping and surveying to stock trading, power grids, and emergency response. However, the satellite-based signals that GPS depends on have known inconsistencies and lack encryption. Compromised, corrupted, or hacked GPS receivers and signals have already caused major disruptions in aviation and government operations, impacting substantial segments of the global economy.

“As we’ve seen in the last few years, GPS is not resilient at all,” Agrawal stated. “You can buy something from Amazon for $20 which can jam the GPS in an entire neighborhood.”

Mesa Quantum is tackling PNT resilience and resolving GPS accessibility issues by designing and manufacturing next-generation quantum sensors, incorporating chip-scale atomic clocks.

“One approach to solving that problem, which is very promising, is if we could build really tiny atomic clocks that we could integrate in our hardware,” Agrawal said. “So we wouldn’t have to rely completely on such a weak signal that is jammable. So that is what we’re trying to do.”

From Lab to Launch

Agrawal and her team are successfully translating sophisticated lab research from CU Boulder into practical quantum solutions ready for deployment. The core technology originates from the lab of Svenja Knappe (CU Boulder Paul M. Rady Mechanical Engineering, NIST), whose work has focused on miniaturized quantum sensors and systems for over two decades. CU Boulder boasts a rich history of quantum innovation, spanning 60 years, including four Nobel laureates. Mesa Quantum is licensing this technology from the university, receiving support from Venture Partners at CU Boulder, and working to shrink components and mass-produce them while driving down costs. The goal is to improve accessibility of their sensors for diverse applications. The company anticipates having a working prototype by 2026. Venture Partners also assisted in the launch of the company.

Quantum sensors are precision instruments designed to gather data at the subatomic level. They detect minute changes in time, gravity, temperature, motion, magnetic and electrical fields etc. The precision of Mesa Quantum’s smaller, more cost-effective sensors can be applied in various fields including medical diagnostics, biomedical research, environmental monitoring, and, of course, positioning, navigation, and timing.

By adapting Knappe’s innovative atomic clock, Mesa Quantum is building sensors capable of detecting environmental changes to determine location, direction, and synchronization with other systems. Agrawal envisions her sensors being used wherever highly precise timekeeping is currently needed, such as data centers and autonomous vehicles; in areas where GPS signals are weak, like dense urban centers; and in challenging environments that GPS can’t reach, like underground, underwater, and in secure military operations.

Agrawal emphasized their desire to “meet the market where it is.”

Agrawal’s interest in quantum science originated in high school. Prior to this, she didn’t see herself as an outstanding student. Science piqued her curiosity then and continues to do so.

“Every day I had like 10 questions for the teacher which must have been very annoying,” said Agrawal, “but that’s when I really got interested in science.”

Openness and curiosity have been critical to Agrawal’s success. She grew up in a small town in rural India, often going to a café to access the internet or staying home to read H.G. Wells’ “The Time Machine” or watch “Stephen Hawking’s Universe.” Agrawal also values the willingness to make mistakes and continue learning.

“It’s not the end of the world if something doesn’t work,” she said. “But I would regret not trying.”

During her PhD studies in quantum information science, Agrawal explored ways to use quantum technologies to bring about positive change.

“I got exposed to a lot of incredible research being done at JILA and NIST in quantum sensing,” she said, “And I got the bug for the impact that quantum technologies could have to actually solve real world challenges.”

At the time, Agrawal did not have a specific concept in mind which she believes gave her flexibility in choosing her focus.

“Because I wasn’t married to a particular idea to begin with, I think that gave me a lot of flexibility,” said Agrawal. “I got quite excited about chip-scale atomic clocks right away because I’d been reading about the GPS problem.”

These experiences led her to channel her quantum knowledge and her passion for solutions into a startup.

The Path to Commercialization

When exploring entrepreneurship, Agrawal turned to Venture Partners at CU Boulder, the commercialization arm of the university. There, she collaborated with Justin Stitzlein, a venture analyst.

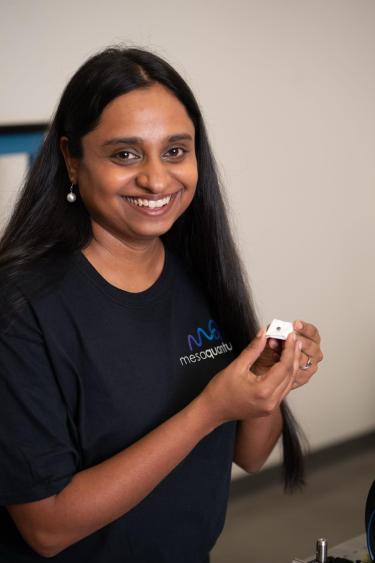

Sristy Agrawal with co-founder Wale Lawal.

Stitzlein was impressed by her background in quantum physics. “Then we provided her with a curated list of potential quantum technologies, she looked through that list and selected one that she thought seemed interesting and that might have a market opportunity,” he said. “Through her research and just a few conversations, Sristy really conceptualized this gap in the market. I don’t think that everyone can do that; she’s such an expansive thinker.”

The path to commercialization can be difficult but Venture Partners helps by connecting industry partners, entrepreneurs, and investors, to transform the discoveries of researchers, inventors, and creators at the University of Colorado into market products.

In late 2022, Agrawal participated in the Venture Partners Starting Blocks Customer Discovery Workshop. This was part of the NSF I-Corps™ Hub: West Region where Mesa Quantum was first conceived. The program assists researchers in establishing a foundation for impactful businesses by pinpointing market needs for their breakthrough technologies using a rigorous customer discovery process. According to Emily Vogt, the director of venture development, “[Sristy’s] chip scale atomic clock technology had broad applications across different industries,”. “Her customer discovery journey through multiple I-Corps programs helped her find the shortest and most compelling path to market, while also highlighting different uses of the technology for future growth.”

During the Starting Blocks program, Stitzlein encouraged Agrawal to focus on the applications of the technology and develop a business model. She then proceeded to create that commercial strategy and meet with prospective customers.

“I’ve never seen someone hit the road as hard as she did,” said Stitzlein.

During this period, Agrawal also took advantage of other Venture Partners programs including the 2023 Lab Venture Challenge (where Mesa Quantum was awarded $125,000) and the 2024 New Venture Challenge Deep Tech Competition (where Mesa Quantum was a finalist). She also participated in New Venture Launch, a Leeds School of Business class for cross-disciplinary teams, individual founders, and entrepreneur-focused students. During this time, Agrawal also developed a partnership with her co-founder and Mesa Quantum’s chief technology officer, Wale Lawal (Harvard, Rice University, U.S. Air Force Academy). Right from the start of her work with Venture Partners, Agrawal felt enormous backing. “I could brainstorm everything with them,” she said.

Venture Partners enabled Agrawal to seamlessly navigate the many opportunities and resources for campus innovators, helping them develop new ventures. Agrawal mentioned that, as an academic, she didn’t have regular access to conversations on entrepreneurship, unlike someone in a business school.

Bryn Rees, the associate vice chancellor for innovation and partnerships at CU Boulder, agreed. “This is definitely a cross-campus collaboration, an example of a founder really leveraging all the different things that this campus has to offer,” he said. “Breaking down siloes is great.” Rees is also looking to see more founders like Sristy—“who’s got that commitment and willingness to try things”—bringing their understanding and passion into the arena of entrepreneurship. Rees views Agrawal and Mesa Quantum as the start of many potential ventures emerging from the university.

“The vast majority of folks don’t know where to start, or don’t have the resources, or don’t have the bandwidth to do that,” he said. “What I think is so exciting about the university now is that for most of the iceberg that’s underwater, for those people who would love to do this if they have support, there are trainings, there are mentors, there’s funding, there’s access to a path to success.”

“Venture Partners created that space for me where I could have those discussions,” Agrawal said. “I cannot overstate how important the community has been in this journey. Mesa Quantum wouldn’t have happened without that support.”