Ai Weiwei’s ‘Rebel’ Exhibition: Art, Activism, and Authority Challenged

World-renowned artist and activist Ai Weiwei is the subject of a major retrospective, his largest exhibition to date in the United States, titled Ai, Rebel: The Art and Activism of Ai Weiwei (March 12 – Sept. 7). The exhibition features photos, sculptures, videos, LEGO-based works, and installations that span the Chinese artist’s illustrious 40-year career. It provides a comprehensive look at how Ai challenges authority, participates in political activism, and questions accepted histories and cultural values.

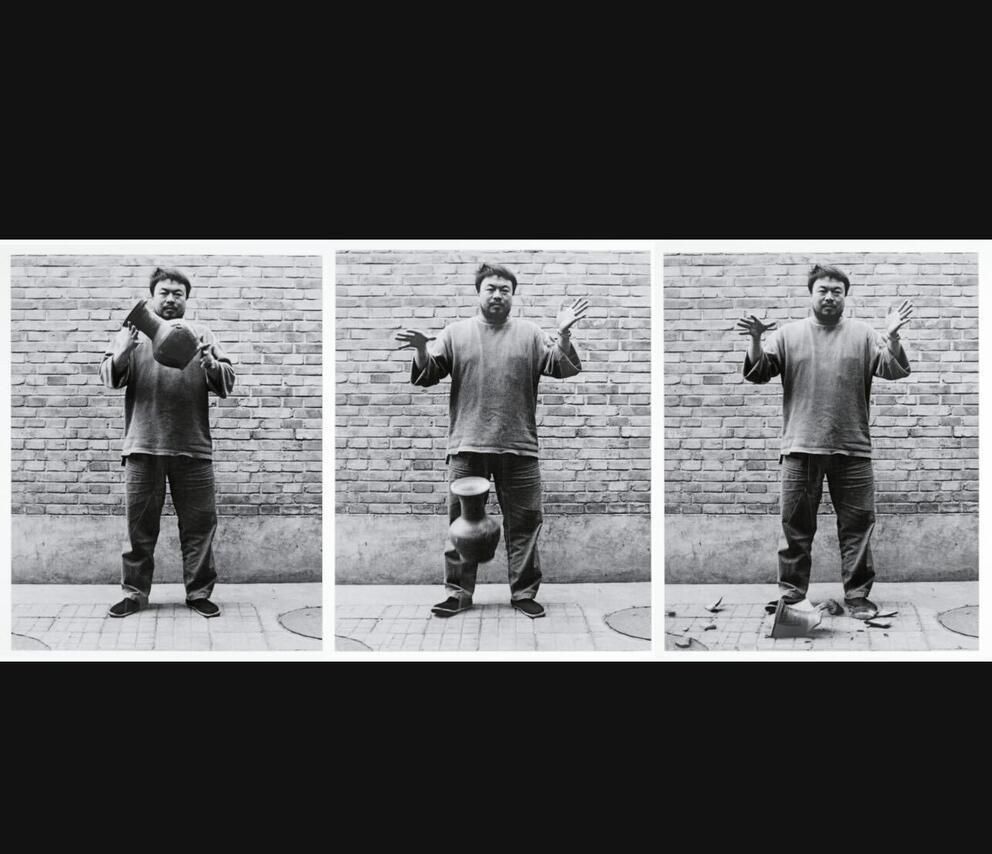

The iconic photo triptych “Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn” (1995) is featured in the exhibit.

SAM’s curator of Chinese art, FOONG Ping, divided the show into three thematically organized galleries which separately explore facets of Ai’s career as a rebel, a material disruptor, and an activist surveilling the state’s surveillance of him. The exhibition title references Isaac Asimov’s science fiction novel I, Robot, as both the book and Ai’s work grapple with the concept of “real.”

The exhibition includes some of Ai’s most renowned works, such as: the iconic photo triptych “Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn” (1995); one ton of hand-painted porcelain sunflower seeds from “Sunflower Seeds” (2010); and Ai-made replicas of Qing-dynasty blue-and-white porcelain vessels. The Seattle Art Museum (SAM) has placed Ai’s fakes among authentic 18th-century blue-and-white porcelain from its collection, challenging visitors to spot the difference.

Also on display are pieces from the artist’s early career. A wall is dedicated to photos of Ai’s time in New York City during the 1980s – dining with Beat poet Allen Ginsberg, and taking photos of New Yorkers. Another section features early oil paintings, including the Warhol-inspired triptych “Mao 1-3” from 1985 and “Safer Sex” (1988), which includes a Chinese army raincoat with a built-in condom.

These early works establish a sense of humanness for an artist with a mythic reputation. Ai’s humor and influences (Marcel Duchamp, Dadaism, Pop Art) are evident in these pieces, though Ai told The New York Times that he felt a little shy about sharing them. “We all have a beginning,” he stated. “The beginning is always pretty clumsy and unprepared. But if you keep working, you may reach some unknown.”

Ai is perhaps best known for his criticisms of the Chinese government. After the 2008 Sichuan earthquake that killed 90,000 people, including thousands of students, he used social media to condemn the government for suppressing the death toll and avoiding responsibility. Works like “Snake Ceiling” (2008), composed of children’s backpacks, and “Names of the Student Earthquake Victims Found by the Citizens’ Investigation” (2008-2011), a detailed list recognizing every student who died in the earthquake, demonstrate Ai taking the investigation and memorialization of the disaster into his own hands.

Over time, the Chinese government repeatedly detained and questioned Ai. In 2011, he was held in an undisclosed cell for 81 days—faithfully recreated in the installation “81” (2013), which visitors may enter. Eventually, Ai left China in 2015 and now divides his time between Berlin and Portugal. He continues to make political art, focusing on the European refugee crisis in pieces like “After the Death of Marat” (2019), a colorful “painting” constructed from LEGOs that references a 2015 photo of 2-year-old Alan Kurdi, who drowned in the Mediterranean Sea while fleeing Syria. In Ai’s version, he places himself as a stand-in for Kurdi, which generated controversy.

Ai, Rebel arrives in the United States at a time of increasing repression. This major exhibit offers a lens through which to examine this moment. As we navigate this period, artists like Ai Weiwei offer perspectives to help us comprehend our world.