Data is the lifeblood of the US tech giants, including Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Apple, Meta (Facebook), Microsoft, and Nvidia. Now, however, these behemoths appear to be turning their attention toward a new frontier: big energy.

These six companies, the world’s largest by market capitalization, are already significant consumers of renewable electricity. But the latest generation of artificial intelligence (AI) systems is multiplying their energy needs, prompting a flurry of deals with energy companies to secure future generating capacity.

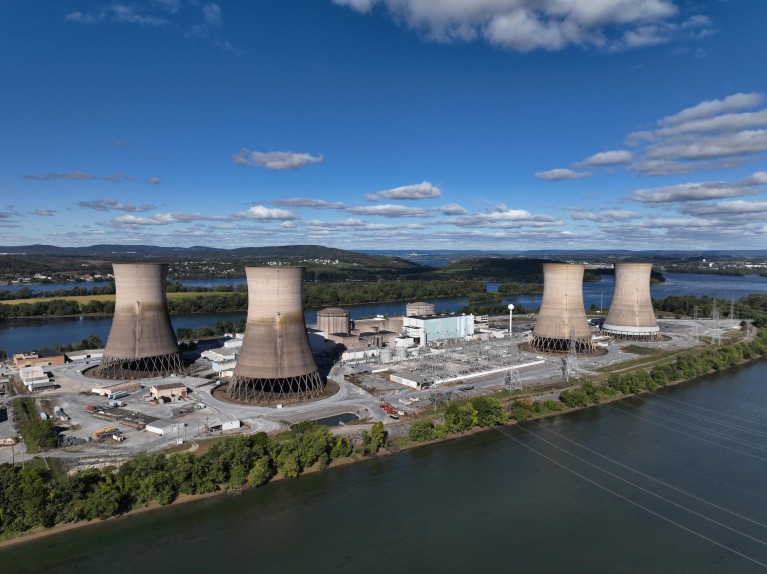

For example, in 2024, Microsoft announced a 20-year agreement to purchase energy from the dormant Three Mile Island nuclear plant in Pennsylvania – site of a 1979 accident – slated to reopen in 2028. Google and Amazon revealed last year that they had signed power purchase agreements (PPAs) with companies developing a new generation of small modular reactors (SMRs). Google and Meta are also putting funds into firms working on next-generation geothermal energy.

These high-profile investments have generated media buzz, accompanied by speculation that they will accelerate the global switch to cleaner power. However, many researchers highlight that the big-tech industry is influencing the energy transition in more significant ways through its cloud computing services, the application of machine learning to electricity supply and demand management, and data harvesting and use.

“In general, it’s better to have them doing all this than actively opposing the transition,” commented Silvia Weko, a sustainability researcher at the University of Erlangen–Nuremberg in Germany. Nevertheless, she and others caution that energy systems risk becoming too reliant on a small number of companies. “Once they have that monopoly, they can do whatever they want with it.”

The big-tech industry has a long history of building renewable-energy capacity to meet its needs. Amazon, for example, owns roughly 25 gigawatts of installed capacity worldwide, mostly solar panels, with some wind power. This total is similar to the entire solar power capacity of the Netherlands. However, the company purchases even more renewable energy from external suppliers through PPAs. These are long-term contracts to buy energy at a fixed price. Amazon has signed contracts for at least 33.6 gigawatts, according to the energy consultancy BloombergNEF.

Sasha Luccioni, who studies the environmental impact of AI at Hugging Face in New York City, notes that this approach generally kept up with big tech’s growing energy needs until about five years ago. “They were on track until generative AI came along,” she said. “I think that with the advent of these new, more energy-intensive models, the PPAs are not enough and now they’re turning to nuclear and other ways of dealing with it.”

The Demand for Power

Generative AI is a type of machine learning that can be trained to recognize patterns within data to produce new text, images, and video. “It’s still this big pattern-recognition engine, but now these models are being trained on all of the internet,” says Raghavendra Selvan, a machine-learning researcher at the University of Copenhagen.

Training a model with billions of parameters can take months at energy-intensive data centers. Once models are available, each query can demand ten times more energy than a conventional web search. Researchers believe these energy costs can be cut. For example, in January, the Chinese AI firm DeepSeek released a chatbot application based on its low-cost R1 model, which requires far less computing power than rivals such as OpenAI.

However, the rapid advancement of AI means that finding a constant and dependable power source for data centers is a growing challenge, particularly since solar and wind power are intermittent.

Geothermal’s Potential

Next-generation geothermal systems could provide a solution. Conventional geothermal systems tap reservoirs of hot water underground, which creates steam to drive turbines. However, there are relatively few places on the planet with the right combination of heat, fluid, and rock permeability, says Lauren Boyd, a geologist who leads the Geothermal Technologies Office at the US Department of Energy (DoE).

Next-generation geothermal systems aim to overcome this limitation by engineering suitable subsurface conditions, either through a process similar to fracking or by drilling angled boreholes deep underground. Both techniques create a route for cool water to be pumped underground, where it absorbs heat before returning to the surface for use in a power station. This should open up many more sites to turn geothermal energy into electrical power, and the DoE estimates that operators in the United States could develop 90–130 gigawatts of geothermal power capacity by 2050.

Boyd says that while these cutting-edge geothermal systems may be more expensive than solar or wind, they provide advantages beyond a consistent power source. They require less land, allowing them to be built where space is limited. They also use materials and technologies that can be sourced within the United States, an important political factor given that China dominates the solar material supply chain.

The combination of public and private financing for next-generation geothermal start-ups like Fervo Energy and Sage Geosystems—both based in Houston, Texas, and partnered with Google and Meta, respectively—helped triple geothermal investment in the United States from 2023 to 2024. “Right now, the number of companies and start-ups in this space in the United States is pretty dramatic,” says Boyd. That puts the United States in a strong position in the race for next-generation geothermal power, although other countries, including France, Germany, Japan, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom, have similar programs.

Nuclear’s Role

Meanwhile, big tech’s investments in SMRs are supporting a technology that many governments believe will aid their decarbonization plans. Proponents argue that these reactors can be manufactured in factories and assembled “modularly” to reduce the cost of nuclear power. Though major SMR developers like Toshiba and Rolls Royce are involved, a wave of start-ups hope to capitalize on the technology. However, no commercial SMRs are currently operational.

Allison Macfarlane, director of the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs at the University of British Columbia, and former chair of the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission, doubts whether SMRs will offer economic advantages over conventional nuclear reactors and suggests they could generate more nuclear waste, raising costs. “With nuclear, it’s always the price tag that kills it, and there’s nothing different about small modular reactors,” she argues.

Macfarlane believes that restarting dormant nuclear plants could be more viable. This is the strategy Constellation Energy in Baltimore, Maryland, has employed with the Three Mile Island plant, which will power Microsoft’s data centers. “That’s the one model that I see as being successful,” she says. However, she cautions that few suitable sites exist in the United States for this kind of project.

The Power Play

Weko and other researchers see big tech’s investments in these technologies as more than a quest for energy; instead, they represent a broader business strategy to play key roles throughout the energy transition, from individual homes to national grids.

Many use Amazon’s cloud-based AI assistant Alexa to manage home energy use. Weko has detailed how global energy-related companies rely on Amazon Web Services (AWS), the largest cloud computing firm with approximately 30% of market share. AWS servers manage energy supply, demand, and storage data, weather patterns, and other factors. AWS also employs machine-learning systems to analyze this data to predict and potentially optimize renewable-energy production. “If you increase the amount of solar and wind on the grid, then it just gets more complex to control because you need to match supply and demand,” says Lynn Kaack, who studies the relationship between AI and climate change at the Hertie School in Berlin, and is also the co-founder of non-governmental organization Climate Change AI.