Introduction

Global electricity demand reached an estimated 28,000 TWh annually by 2023. This demand continues to grow, with projections indicating a potential doubling by 2050. Growth rates vary geographically, influenced by population increases, industrialization, and electrification trends. In India, for instance, demand surged to 185 GW and is anticipated to surpass 330 GW by 2030.

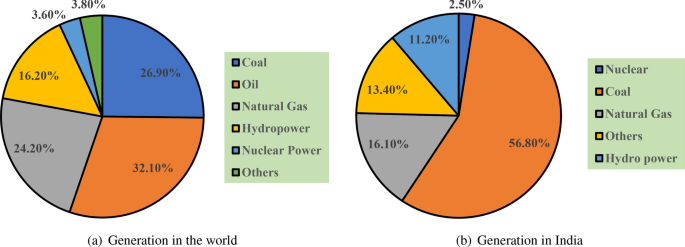

This energy demand is primarily met by conventional power systems that often rely on non-renewable energy sources. Globally, the primary energy mix includes oil (32%), coal (26.9%), and natural gas (24.2%), with other sources accounting for the remaining 23.6% (Figure 1a). The proportions vary regionally; Figure 1b illustrates India’s energy source distribution.

Conventional energy systems relying on non-renewable resources pose several challenges. These resources are non-replenishable within human lifespans, generate pollution upon combustion, and create hazards during extraction. Furthermore, their prices are subject to volatility stemming from geopolitical tensions, political factors, and supply chain disruptions.

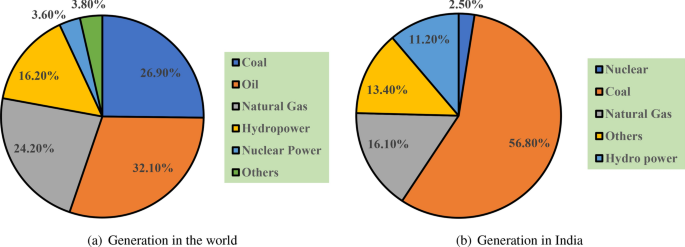

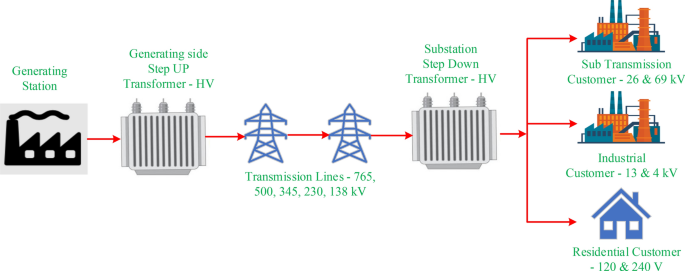

Conventional energy systems often rely on long-distance transmission lines for power distribution, leading to energy losses during transmission. These losses vary from region to region; in India, transmission losses were around 17% in 2023 (Figure 2), according to the Central Electricity Authority. The construction and maintenance costs of these long-distance lines are substantial, and they are susceptible to faults due to environmental and non-environmental factors. These faults result in electricity supply disruptions and, consequently, consumer inconvenience. The conventional system is also vulnerable to electricity theft. Moreover, these systems lack a mechanism to verify the amount of electricity received by the end-user, which can lead to discrepancies and financial losses. The use and combustion of fossil fuels result in pollution, leading to an urgent global need to adopt alternative energy sources.

Governments worldwide are advocating for greener and renewable energy sources. In India, government initiatives such as the National Solar Mission, the National Wind Energy Mission, and Green Energy Corridors aim to add 450 GW of renewable energy (RE) production by 2030 and achieve 40% of the nation’s energy demand from renewable sources. RE sources are inexhaustible, are not known to cause ecological or health risks, and have relatively stable prices. Moreover, renewable energy generation is often closer to the point of consumption, which eliminates the need for long-distance transmission lines and related challenges.

Renewable energy sources are weather-dependent and variable, which affects grid stability and requires energy backup for a consistent supply. They also require specialized equipment for installation and technical expertise for maintenance, which can make their implementation costly. To effectively utilize RE and overcome its variability, network participants should be able to use or store the electricity when it is produced. Peer-to-peer (P2P) trading can facilitate more effective energy consumption since effective energy storage mechanisms are not in place. This would involve a multi-directional flow and control of energy to avoid congestion points. P2P trading enables prosumers (those who both produce and consume energy) and consumers (those who solely consume energy) to engage in direct energy exchanges, thereby bypassing the traditional grid. This minimizes distribution losses and enhances system efficiency, while also fostering market competition and potentially reducing energy costs.

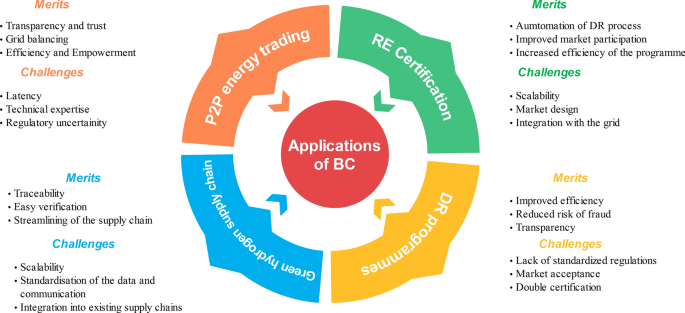

A secure and reliable communication framework is essential for P2P trading. All network participants need access to real-time data on all producers and prosumers regarding electricity production, storage, and consumer consumption patterns. A key challenge is addressing malicious actors who might pose as producers to defraud consumers. The exchange of funds and electricity should be synchronous to minimize potential losses. P2P trading also involves the installation of smart meters, which increase initial costs. Blockchain (BC) technology emerges as a potential solution, aiming to ensure secure and transparent transactions due to its distributed and decentralized ledger. Since data related to each block and the transaction is stored on all participating nodes, it eliminates the need for intermediaries. Blockchain enhances system security and dependability by removing these intermediaries, ensuring inviolable transaction records and transparency to mitigate the potential for corruption or fraud. It can facilitate P2P trading, secure green hydrogen supply chains, manage Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs), and enable real-time Demand Response (DR) mechanisms.

This article explores four key application areas of BC in the energy sector: P2P energy trading, the green hydrogen supply chain, RECs, and real-time DR mechanisms. The article compares existing projects in P2P trading, identifies the merits and challenges, and outlines the use of BC in administering green hydrogen supply chains while maintaining supply chain security and traceability. BC’s use is also examined in issuing, verifying, and storing RECs, as well as tracing and controlling DR within the grid and incentivizing consumers to participate in DR initiatives.

Blockchain

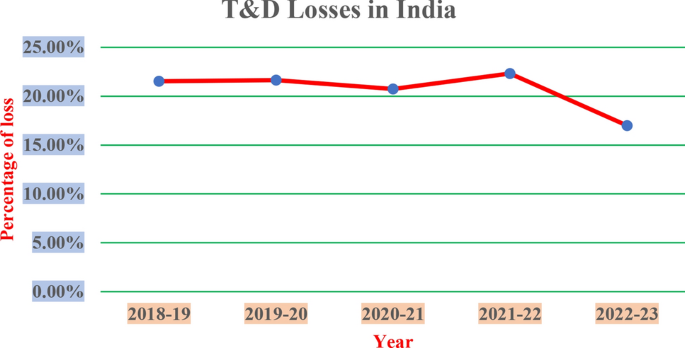

Blockchain is a cryptographically secure, distributed, immutable, and decentralized ledger. It operates on a P2P network where updates require consensus among nodes, without a central server. Data is added sequentially and chronologically to the blockchain, and once added, it is almost impossible to modify without the approval of every node in the network. A blockchain consists of blocks linked together with a unique identifier. Figure 3 elucidates the contents of a single block.

Blocks

A block contains a collection of transactions divided into the block body and block header. The header includes a timestamp, block number, Merkel tree, nonce, and the previous block’s hash, while the body contains all transactions. The first block is known as the genesis block. The nonce is a random number used during block creation to find a hash that satisfies the chain criteria. Miners generate a hash by including the nonce with new block data. A timestamp ensures the chronological order of transactions and protects the BC from transaction repetition or order manipulation. A Merkel tree is the hash of all hash values within that block. BCs use hashes to establish privacy and security. A hash is a unique digital fingerprint for data; even small data changes result in a completely different hash. The hash of a block is calculated using all the data in the block, including transaction data and the hash of the previous block. The current block is linked to the previous block through the previous block’s hash. Hashes are created by cryptographic hash functions, producing an alphanumeric output of a fixed length.

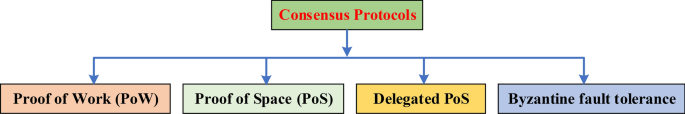

Consensus Protocols

Consensus protocols ensure mutual agreement on the state of the chain and validate network transactions; this prevents transaction repetition and other hazards (Figure 4). There are several consensus protocols, with a comparison in Table 1.

- Proof of Work (PoW): New nodes solve a cryptographic puzzle. The first to complete the puzzle joins the network. Used in Bitcoin.

- Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT): Allows consensus even with malicious nodes. If over 50% of nodes agree, the transaction is allowed. Used in Neo and Tendermint.

- Proof of Stake (PoS): Nodes hold a stake in the currency. Larger stakes increase the chance of being selected to validate transactions. Commonly used in Cardano and Ethereum.

- Delegated Proof of Stake (DPoS): Users choose nodes based on their confirmation promises. Used in EOS and Steem.

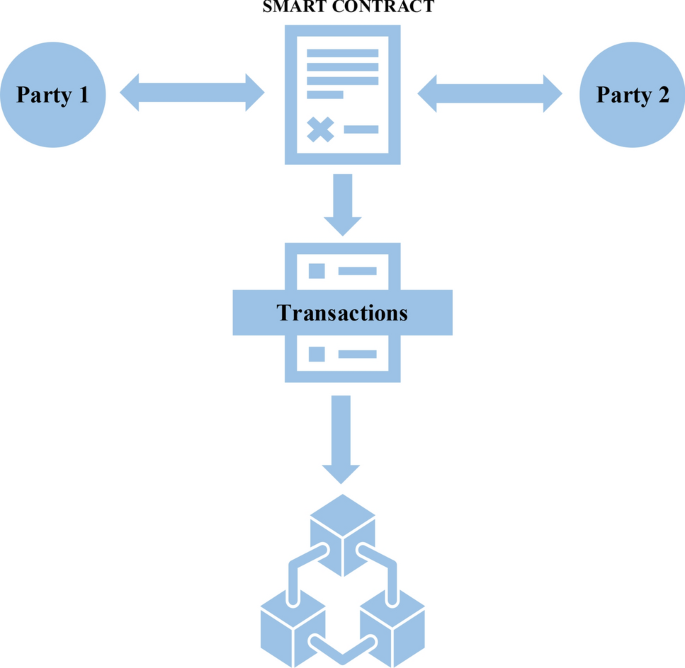

Smart contract

A smart contract (SC) is a self-executing electronic code stored on the network, an agreement that automatically executes the terms and conditions between two or more parties. SCs are immutable, transparent, and resistant to fraud and tampering. SCs eliminate the need for intermediaries, decreasing transaction costs and increasing efficiency. The working of SCs is demonstrated in Figure 5.

SCs function on decentralized platforms like Ethereum, using BC to record and authenticate transactions. They are employed in applications that rely on high levels of trust and transparency, such as financial transactions, supply chain management, and creating decentralized finance (DeFi) protocols to automate borrowing and lending. In supply chain management, Smart Contracts enhance traceability and automate payments upon successful delivery. In the energy sector, BC and SCs offer solutions for P2P trading and decentralizing the entire energy landscape and also secure the green hydrogen supply chains and help to issue RECs. Smart Contracts reduce the possibility of disputes by executing clauses in response to predefined conditions.

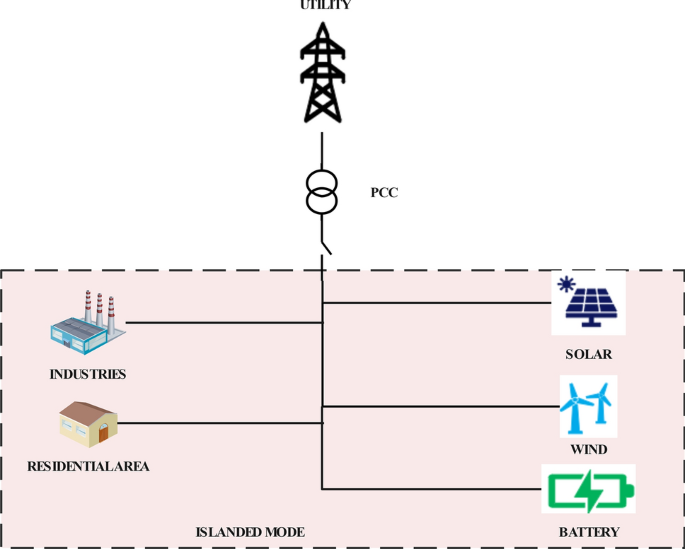

Microgrid

Microgrids are localized energy systems comprising distributed energy resources (DERs), power generation sources and loads interconnected within a defined boundary, operating independently or with the main power grid. They include two modes of working: islanded and grid-connected. A microgrid has various key factors.

- Localised power generation: Solar, wind, or hydroelectric generators are located near the load.

- Energy storage: Technologies like flywheels or batteries store electricity during low-demand periods for use later.

- Control and management system: Manages power flow and coordinates generation sources while managing energy storage.

- Islanding capability: Operates independently during outages.

- Grid interconnection: Can connect to the main grid to exchange electricity.

- Load management: Involves optimizing energy consumption, DR strategies, and load shedding.

- Resilience and reliability: Enhances grid resilience and reliability.

- RE integration: Designed to integrate RE sources, reducing reliance on fossil fuels.

Smart grid

Smart grids use communication protocols and automation to acquire real-time data by upgrading microgrids. Unlike conventional grids, smart grids use technologies like real-time communication facilitating exchange of data and control across its components. The foundation of a smart grid is the Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI). In the distribution automation phase, smart grids employ intelligent devices, sensors, communication devices, and networks to manage and monitor electricity flow (Table 2).

Applications of blockchain in the energy sector

BC can transform the energy landscape due to its decentralised and transparent nature. It can facilitate P2P energy trading seamlessly and help integrate RE efficiently. BC can also be used in emerging energy technologies like green hydrogen. By using BC, the energy sector can become a more sustainable and decentralized energy ecosystem.

Energy trading

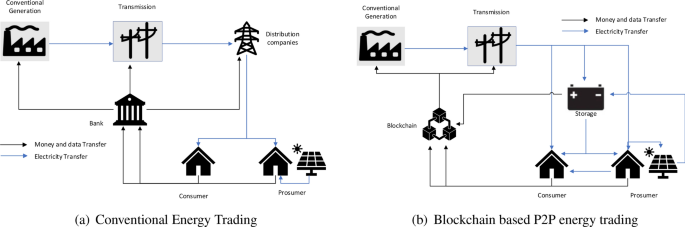

In the conventional grid (Figure 8a), energy trading is centralized, with intermediaries, such as banks and energy corporations, receiving the electricity from the main grid. Banks act as the central authority for all of the monetary transactions, and verification of these transactions takes a very long time.

Using the BC, as shown in Figure 8b, enables the creation of P2P electricity marketplaces. Consumers can directly trade excess energy with one another. Decentralization gives consumers more control and promotes the use of DERs. Smart meters and BC provide real-time data on energy availability between each prosumer and consumer.

Various BC platforms using different consensus protocols can facilitate trustworthy and secure transactions in the grid, since BC greatly amplifies security, transparency, and efficiency. For energy trading in microgrids, the primary use case of BC is P2P trading.

Green hydrogen supply chain

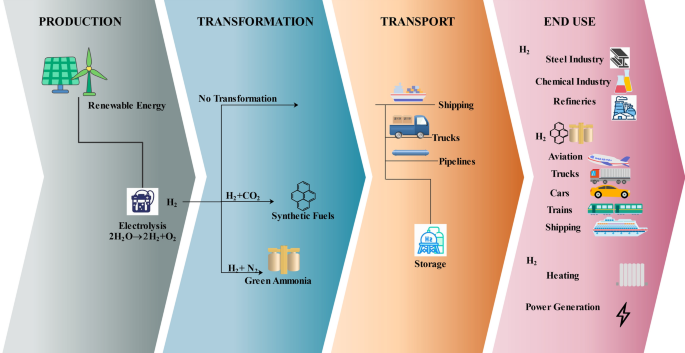

The green hydrogen supply chain is a complex one consisting of production, transportation, and utilization phases. From production to distribution, the carbon footprint data is recorded on the blockchain that guarantees adherence to environmental requirements (Figure 10).

Real-time demand response

DR is a key tool that enables microgrid operators to optimize energy utilization and enhance grid reliability. The main challenge is securing consumer participation. Although some users might be incentivized to join the DR programme, convincing others to change the consumption habits they are accustomed to requires targeted outreach and education programmes. By employing BC, a secure and transparent record of energy consumption and associated incentives can be stored immutably, thereby fostering trust and encouraging broader consumer participation.

Renewable energy certificates

RECs provide a solution to incentivize the development of RE and ensure environmental attributes are properly accounted for. These can be vulnerable to fraud and duplication. BC ensures transparency and reduces the risk of duplication or manipulation. SCs can automate processes and streamline administrative procedures and transaction costs (Figure 11).

Conclusion

Blockchain technology, with its transparency and immutability, can secure data robustly and overcome challenges faced by traditional energy markets. In P2P energy trading, the green hydrogen supply chain, real-time DR, or REC markets, blockchain offers benefits. The existing blockchain technologies do, however, have several current challenges, notably in scalability, latency, interoperability between several blockchain technologies, and regulatory compliance.

Future scope

Developing Layer-2 blockchain solutions, working on consensus algorithms like PoS, are more energy-efficient. Interoperability and interconnection between different blockchain platforms, along with government regulation, are necessary for the effective use of this technology. Integration of DR, P2P trading, and RECs can enhance the sustainability of the energy market.