The Impact of AI on Women’s Employment in Europe

Technological advancements consistently reshape the jobs people do, often leading to shifts in employment distribution. Skill-biased technological changes in the 1970s and 1980s increased demand for educated workers, while automation, starting in the 1990s, reduced demand for routine jobs. These technologies have also affected men and women differently.

Historically, women benefited from mechanization and skill-biased technological change due to their comparative advantages in intellectual activities compared to physical labor (Galor and Weil 2000). Although women have been more affected by automation (Cortes and Pan 2019, Albanesi and Kim 2021), their educational gains and interpersonal skills have allowed them to transition into professional roles and make employment gains, while men have shifted into lower-level service jobs (Cortes et al. 2024).

The latest wave of innovation is driven by artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled technologies. These technologies employ algorithms that learn from data to automate tasks, including non-routine and creative jobs, in manufacturing and services.

In a recent paper, Albanesi et al. (2023) analyzed the relationship between AI-enabled technologies and employment in various sectors across 16 European countries (Austria, Belgium, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and the UK) between 2011 and 2019. The study showed that occupations with higher exposure to AI-enabled technologies experienced a rise in their employment share.

AI’s Differential Impact by Gender

A key question is how these technologies impact women and men differently. To examine this, Albanesi et al. (2025b) investigated the association between AI-enabled technologies and the share of female employment in the same countries over the same period. They analyzed data at the three-digit occupation level from the Eurostat Labour Force Survey and measured exposure to AI using two existing measures developed for the US.

The first measure is the AI Occupational Impact score from Felten et al. (2019), which connects advancements in AI, such as finding patterns in data, to the abilities required by each occupation. The second measure, from Webb (2020), quantifies AI exposure based on how much the descriptions of an occupation overlap with the language used in AI-related patents. These measures indicate the extent to which occupations could be automated by AI.

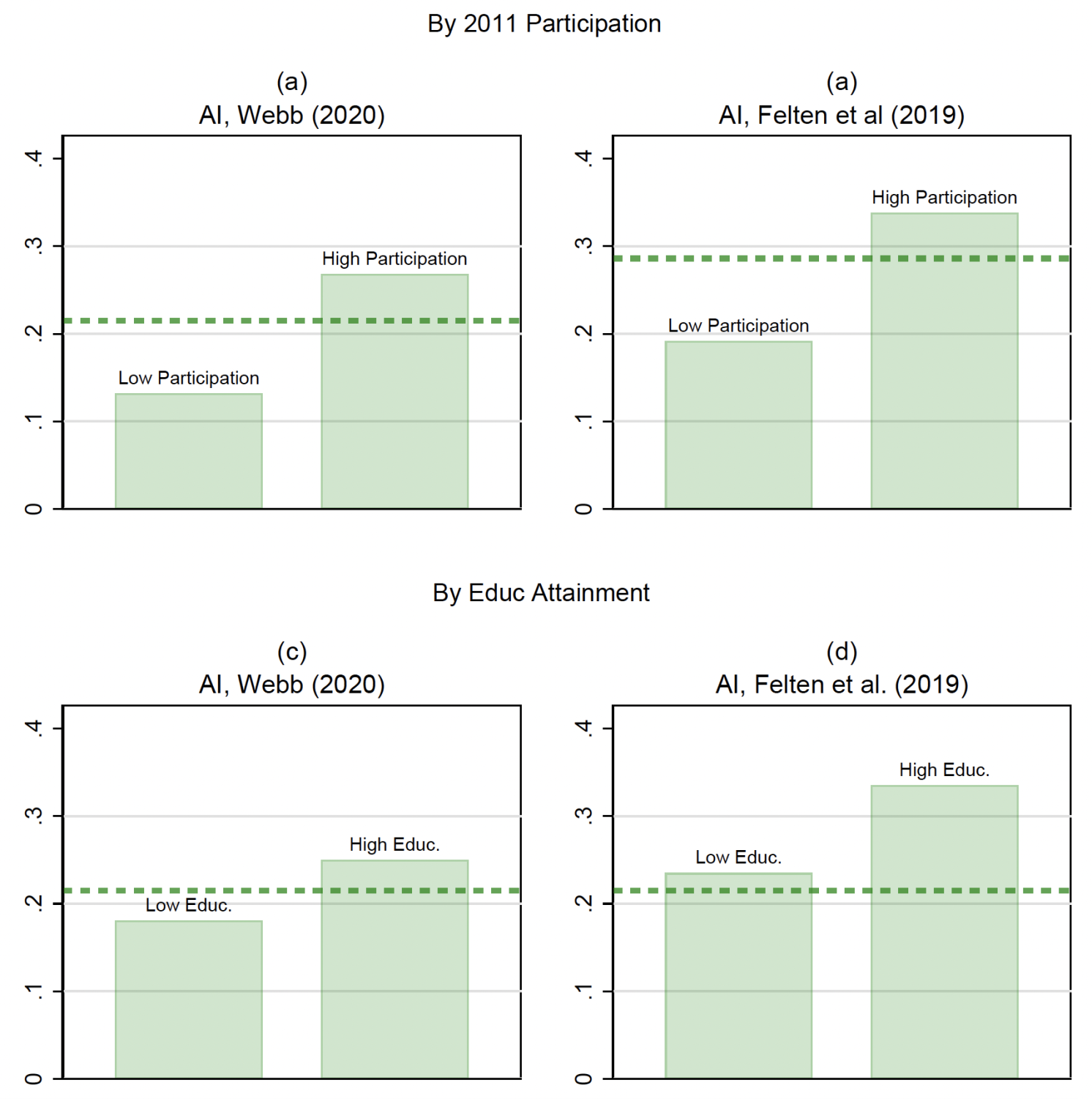

Both measures revealed that higher exposure to AI correlated with an increase in the share of overall female employment. On average, a 10-centile increase in exposure was associated with a 2.2%–2.9% rise in female employment share, which is roughly double the effect on total employment share found in Albanesi et al. (2023, 2025a). Furthermore, the positive correlation between AI exposure and female employment share was more consistent across occupations than the association between AI exposure and overall employment share, which was mostly driven by professional occupations.

Education’s Role

Educational attainment plays a significant role in how new technologies affect employment, with highly educated workers generally benefitting most (Albanesi et al. 2023, 2025a). Considering the wide variation in women’s educational attainment across the studied countries, the researchers stratified their results based on each country’s average female educational attainment.

They found a stronger link between AI exposure and the proportion of women employed in countries where women’s educational attainment had increased the most. In those countries, a 10-centile increase in exposure to AI was associated with a 2.7% increase in the female employment share, as measured by Webb’s exposure metric, and a 3.4% increase when using Felten et al.’s measure.

Figure 1: Exposure to AI and changes in female employment shares, by female participation and education

Labour Market Attachment

Greater attachment to the labor force is also a key factor. Countries with initially lower female participation rates exhibited stronger positive trends in female employment growth. To account for this, the analysis was separated by women’s labor force participation rates in 2011. The results indicated that the association between female employment share and AI exposure was stronger in countries with high initial levels of female participation across both AI exposure metrics.

This pattern suggests that a stronger attachment to the labor force enables women to better manage the displacement effects associated with the deployment of such technologies.

Conclusion

In summary, the findings support the idea that AI-enabled technologies can benefit women’s employment, particularly when combined with higher levels of education. Additionally, the positive association between female employment and AI exposure is stronger in countries where women’s initial labor force participation is higher, which indicates that greater labor force attachment and work experience allow women to lessen any adverse effects from the introduction of new technologies.

These findings also align with UNESCO’s (2022) view: having the right educational credentials is key to unlocking any advantages that AI might offer to women’s job prospects.

Authors’ note: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the ECB, the Banco de España or the Eurosystem.

References

- Acemoglu, D (2020), “Technical change, inequality, and the labor market”, Journal of Economic Literature 40(1): 7–72.

- Acemoglu, D, N S Mühlbach, and A J Scott (2022), “The rise of age-friendly jobs”, NBER Working Paper 30463.

- Albanesi, S, A Dias da Silva, J F Jimeno, A Lamo, and A Wabitsch (2023), “Artificial intelligence and jobs: Evidence from Europe”, VoxEU.org, 29 July.

- Albanesi, S, A Dias da Silva, J F Jimeno, A Lamo, and A Wabitsch (2025a), “New technologies and jobs in Europe”, Economic Policy 40(121): 71–139.

- Albanesi, S, A Dias da Silva, J F Jimeno, A Lamo, and A Wabitsch (2025b), “AI and Women’s employment in Europe”, AEA Papers and Proceedings 2025 115: 1–5.

- Albanesi, S, and J Kim (2021), “Effects of the COVID-19 recession on the US labor market: Occupation, family, and gender”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 35(3): 3–24.

- Albanesi, S, and A Sahin (2018), “The gender unemployment gap”, Review of Economic Dynamics 30: 47–67.

- Autor, D, L Katz, and A Krueger (1998), “Computing inequality: Have computers changed the labour market?”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 113(4): 1169–213.

- Autor, D H, and L F Katz (1999), “Changes in the wage structure and earnings inequality”, Handbook of Labor Economics 3(A): 1463–555.

- Autor, D H, F Levy, and R J Murnane (2003), “The skill content of recent technological change: An empirical exploration”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(4): 1279–333.

- Cortes, P, Y Feng, N Guida-Johnson, and J Pan (2024), “Automation and gender: Implications for occupational segregation and the gender skill gap”, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Cortes, P, and J Pan (2019), “Gender, occupational segregation, and automation”, Economics Studies at Brookings.

- Felten, E, M Raj, and R Seamans (2019), “The effect of artificial intelligence on human labor: An ability-based approach”, Academy of Management Proceedings.

- Galor, O, and D N Weil (2000), “Population, technology, and growth: From Malthusian stagnation to the demographic transition and beyond”, American Economic Review 90(4): 806–28.

- Goos, M, and A Manning (2007), “Lousy and lovely jobs: The rising polarization of work in Britain”, Review of Economics and Statistics 89(1): 118–33.

- UNESCO (2022), The effects of AI on the working lives of women, UNESCO/OECD/IDB.

- Webb, M (2020), “The impact of artificial intelligence on the labor market”, working paper.