The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) recently published its ‘Design for Life Roadmap,’ a policy paper outlining the development of a circular economy for medical technology. A crucial question is whether the proposed timescales are ambitious enough to drive meaningful change.

The Design for Life Roadmap

The 2024 policy paper, officially titled ‘Design for Life Roadmap – Building a circular economy for medical technology,’ outlines 30 ‘actions’ organized under six ‘problem statements.’ The DHSC aims to address these challenges to establish a circular system. The target for a fully functional circular system is 2045, which many in the medtech industry believe is too far off. Many medtech companies are already making strides in this direction, and the public sector needs to change with urgency.

The Case for a Circular Economy

The arguments for medical technology circularity are compelling:

- Economic Benefits: A circular system could ensure that more of the £10 billion the NHS spends on medical devices remains within the UK.

- Supply Chain Resilience: Circularity reduces reliance on potentially unstable global supply chains and fosters local capacity to meet demand, protecting health systems from global supply shocks.

- Environmental Advantages: Circular approaches will minimize waste and carbon emissions. For example, the NHS discards 133,000 tonnes of plastic annually, roughly equivalent to all household waste generated in Leicester, but currently recycles only a small portion.

- Cost-Effectiveness: Circular devices are frequently more cost-effective than single-use alternatives, with case studies showing savings of over 50% compared to conventional equivalents.

Roadmap Timelines – A Sense of Urgency?

The Roadmap’s actions are categorized by maturity, with high-maturity actions targeted for completion between 2024 and 2027, medium-maturity actions from 2027 to 2029, and low-maturity actions scheduled for 2029-2031. Currently, only three actions are classified as high-maturity, with the DHSC citing the need for significant research before progressing with others.

The initial three actions, set to be completed in the next three years, involve collaborating with other policymaking bodies, presenting a full ecosystem roadmap, and embedding medtech circularity in communications and strategies. While the paper identifies behavioral change as the key challenge for clinicians and patients, the action to develop a behavioural change plan is not scheduled until the 2029-2031 window which appears too late.

Other actions delayed until the same timeframe include “Develop a decontamination infrastructure framework” and “Establish a materials recovery and recycling framework.” These structures are already within existing local council resources. The NHS potentially could implement these actions sooner.

Barriers to Change

The paper clearly identifies challenges related to change. Procurement practices are hindered by short-term budget constraints. Short-term planning often favors lower upfront costs over long-term value. Procurement behavior will not change while these drivers remain in place. NHS Supply Chain agreements will likely continue to focus on established practices, with descriptions rather than focusing on clinical outcomes or lifetime cost benefits.

Existing Solutions

Many solutions exist for the building of a circular economy system. Dr. Barend ter Haar, involved in seating and mobility for over 30 years, points out many areas where solutions have been available across the circular economy system:

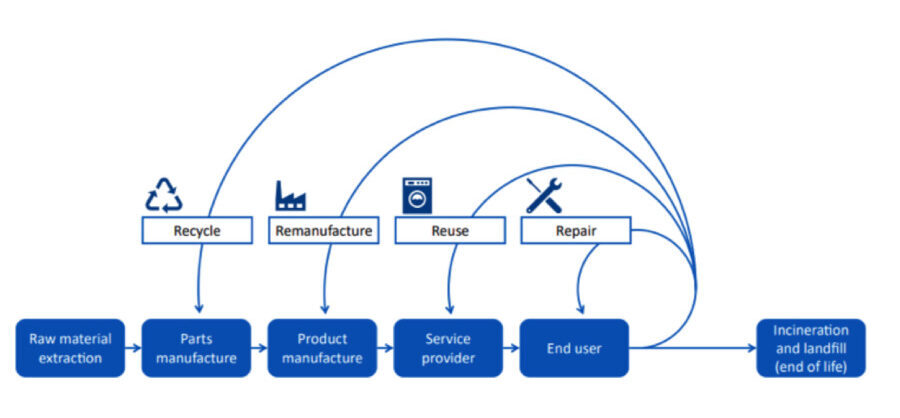

- Recycle: BES Healthcare has been selling washer-disinfection machines for nearly three decades, and, when these machines are upgraded, they either refurbish older models for reuse, or strip them down so that stainless steel can be recycled. The NEST mattress and cushion line offers cores that can be washed, disinfected, and reused for up to eight years. Once the mattress is no longer usable, it can be shredded and recycled back into its original plastic core.

- Remanufacture: The assistive technology industry frequently provides equipment, like adjustable children’s equipment, that meets changing needs. John Prout modified the Scandinavian Tripp Trapp high chair to make it safer for youngsters with mild physical challenges, creating the Breezi range. These chairs can be adjusted for individual needs. Components can also be replaced or upgraded without needing a completely new item.

- Repair and Reuse: Wheelchair services and loan stores offer repair and reuse services, with the community side of the NHS leading the way. These stores utilize automated washer-disinfectors for efficient and repeatable cleaning and disinfection, protecting staff from infection. Regulations like the MDR now require CE-marked medical devices to be decontaminated only with chemicals and equipment also CE-marked medical devices. New standards such as those in the BS EN ISO 15883 series help direct decontamination.

- Usable life: The development of equipment that extends the functional lifespan is vital The Cascade Designs Varilite range of cushions, utilizes technology from ThermaRest camping mattresses. They place foam in an adjustable airtight bag that is designed to extend the life of the foam. Bodypoint belts and harnesses were designed to meet ISO 16840-3 performance tests, and their durability reduced the volume of orders. High quality products can last for a long time. The Matrix seating system, now also available in the updated FreeForm seating system, employs adjustable components that allow users to adapt to meeting their needs for the duration of their lives. The system is lightweight with re-useable components.

Conclusion

The primary care sector is already on the path towards a circular economy, with the acute sector having the opportunity to make accelerated progress by learning from what is already available. The main obstacles need addressing at the outset: these are: the deep-rooted behavioral issues around product specification and prescription, and the short-term drivers of our procurement processes. Adopting a pilot approach may reduce the perceived risks of change, but this approach has had mixed successes. The current goal of 7 years to meet change could be condensed into 3 years – with sufficient initiative.